This store requires javascript to be enabled for some features to work correctly.

The Flâneurs

Flânerie in the design backstage: Piping hot revolutions

I have been continuingly fascinated by metal. This material seems to have the magic power to express ideas that should be mutually exclusive; modernity and nostalgia, mass production and craftsmanship, sensuality and functionality. The use of metal has also achieved nothing less than turning our esthetic and social convictions upside down.

The shift from handcrafted wood furniture to metal pieces is pivotal as it meant that well-designed furniture could be reproduced thousands of times and at a reasonable cost. In other words, this switch paved the way for each of us to live comfortably with great works of design that stimulate the same emotions as the original creation.

By Astrid Malingreau

The great minds at the origin of this revolution were influenced by abstract art (one of the first tubular steel chairs was made by Marcel Breuer for the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky) and social theories of the Bauhaus movement. The inspiration also came through simple observations: The very first prototype of a cantilever chair (the W1) was put together with welded gas pipes by Mart Stam in Stuttgart in 1926.

I discovered that pipes watered other design histories and I would like to take you for a flânerie along another plumbing-inspired revolution.

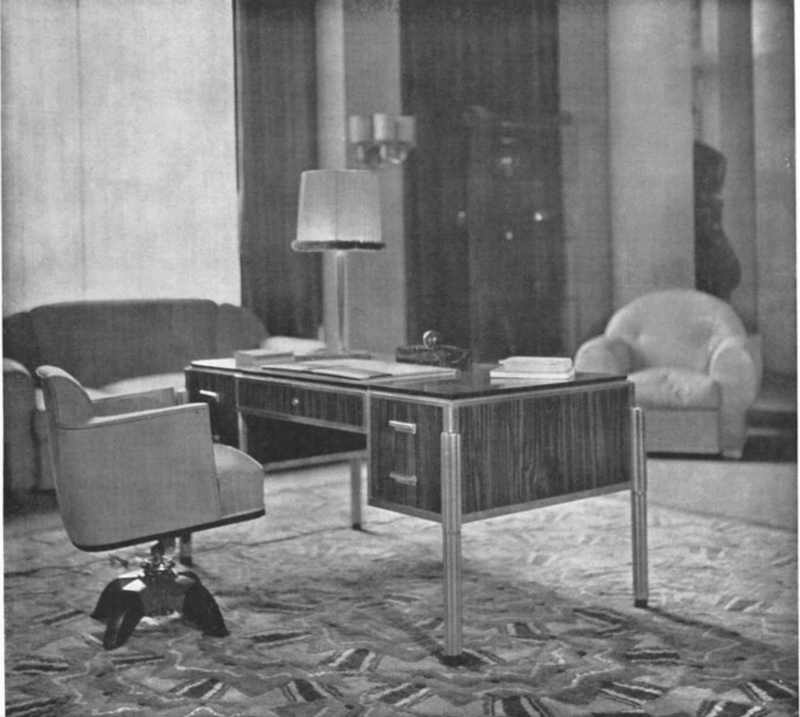

At the 2009 European Fine Art Fair (commonly called Tefaf), the Galerie Vallois presented a booth composed entirely of metal furniture. At its center, a grand semi-circular desk and an armchair that I had never seen but whose design felt familiar. TheBordereldesk and armchair were a prototype designed by the Art deco master Jacques Emile Ruhlmann (1879-1933) and entirely made out ofDuralium(Duralium was originally developed for aviation. It combines the lightness of aluminum and the strength of metal). Ruhlmann was a designer of luxury furniture, known worldwide for his use of opulent materials such as fine woods and inlaid ivory, far from industrial production. For a design geek like me it was surprising to see his name associated with such a metallic ensemble. I had to investigate.

In the 1920s, France was leading the arts worldwide, excelling in the decorative realm with internationally recognized names such as Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann, Eugène Printz and Jean-Michel Frank. At that point the great pride of France was the art of ébénisterie (a word that separates the cabinet maker from the simple woodworker). The unrefined metal was not considered sophisticated enough to be seen bare in the honorable society. Of course elements made out of delicately casted bronze had found their way in the decorative art court but always dressed in a civilized gold or silver coat. And yet, the leading name of the art déco, Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann, ventured into the domain of metal.

You may wonder – as I did – why would the designer take such a daring and forward-thinking decision?

Well, Ruhlmann was an observant man and he saw that society and technology were moving toward more comfort. This comfort came through the apparition of central heating systems (again the pipes…). Wood being a living material, changes in temperature and dryness are its enemies as they cause it to warp. Ruhlmann was assisted in his experimentations by his friend Raymond Subes (1891-1970) who was the artistic director of the Borderel et Robert, a company specialized in ironwork.

In 1925, he designed a prototype for a chair with an enameled metal frame which was so innovative that it already anticipated the imperatives of mass production (easy to manufacture and with the smallest possible amount of material). This early model offers a strong resemblance with what we consider today to be one of the common stacking chairs. However, Ruhlmann’s prototype was never produced. (We will never know for certain why, but the growing rumors of an extraordinary modernist project distracted him. Indeed in those years, the Maharadja d’Indore was making frequent visits to Paris, with his suite of advisors, to scout the french design horizons and decide who were to be the artists of the Manigh Bagh Palace. But that’s just maybe.)

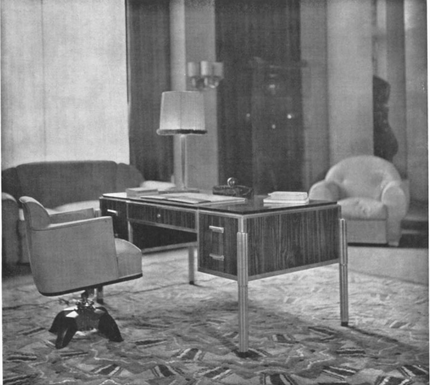

The following year, Ruhlmann presented at theSalon des Artistes Décorateursa desk where each wood panel was framed by shiny silver chromed mounts. Unfortunately, Ruhlmann never lived to see what I saw at the Tefaf…. theBordereldesk and Armchair that were produced in 1933, the year of his passing. With these inventions, Ruhlmann was for the first time using metal as a ‘noble’ material. His creations were limited to private commissions but they certainly played a role in the uncompromising modernity that was about to take over.

In 1929, only a few years after Ruhlmann’s first metal creations, Le Corbusier’s architecture practice (where the future leading figures of French design Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret were working) showed his first seats in bent metal. Metal furniture became more and more easy to produce (and reproduce) and the door of the social revolution became wide open…

Next time you fearlessly turn on the heat sitting in your cantilever chair have a thankful thought for Jacques-Emile.

Cantilever Chair in Steel Frame and Leather S33 Pure Materials

£985

Cubic form, clear design, fine proportions, and flexing movement: the development of the perfected cantilever chairs S 33 and S 34, among the first of their kind, today combines zeitgeist and a sense of tradition. “Why four legs if two will suffice?”, wrote artist Kurt Schwitters in 1927 after seeing the first cantilever chairs in furniture history. The two chairs S 33 and S 34 caused a sensation at the Werkbund exhibit at the Weissenhof Estate in Stuttgart. Starting in 1925, Mart Stam experimented with small diameter gas pipes, and at first he connected them with standard pipe fittings as used by plumbers. As a further development, Stam created cantilevered chairs that no longer stood on four legs, and it was a construction principle that became an important building block in the history of modern furniture design with its formal restraint. His cantilever chairs S 33 and S 34 were more than matter-of-fact designed interior design objects; they were part of the overall revolutionary concept of a new attitude towards architecture and life.